A Roll of the Liar's Dice

01 Dec 2015This post is part of the F# Advent Calendar 2015. Check it out for two F# blog posts a day for the whole month of December. And special thanks to Sergey Tihon for organizing this!

Today I’m going to show you a little bit of game theory modelling with F#. We’ll take a common pub dice game, construct a game tree out of it and then analyze it with the Gambit game theory tool.

No prior knowledge of game theory is needed! Gambit will do the math for us; we just need to familiarise ourselves with some of the concepts to be able to output something it can analyze.

Liar’s dice

In this post, we’ll be analyzing a simple version of the game Liar’s dice. There are two players, each with one die each. They roll their die simultaneously, concealing the result from each other.

Players will now take turns making bets on the collective amount of dice with a certain face. For example, Player 1 could bet that there are at least two dice with the value 3. Player 2 now has two choices. He can call Player 1’s bet, saying he does not believe it to be true. Or he can make a higher bid, and the choice now goes back to Player 1. A higher bid is one where either the die is higher or the amount is higher.

In the case where he calls the bet, the players reveal their dice and it can be checked if the bet was true or false. If it’s true the calling player loses, otherwise he wins.

Game theory

I’ll briefly introduce some concepts we can use to analyze this game. The game theory field is very heavy on notation, so I’ll try to explain the concepts in plain english, without the mathematical rigor.

We’re going to be constructing a game tree, consisting of nodes and edges. Each node can be one of these three types:

- Chance node. This is a node that indicates something random happening. In our case, we’ll use one for modelling the players rolling their dice.

- Decision node. This is a node where a player needs to make a decision on how to proceed. In our case, this will be where the players make their bets, or call their opponents.

- Terminal node. This is a node where the game ends. After the game ends each player will be awarded a payoff. In our case, the game can only end after a player calls a bet.

The edges of the tree indicate an action. An edge out of a chance node represents the result of a random event, while an edge out of a decision node represents a player action.

The flow of the game will be dictated by the relationship of the nodes in the tree. Child nodes happen after their parents.

There’s only one last concept, and that is the information set. Since each player can only see his own die, there will be several nodes in the game tree where he has the same amount of information available to him, but where, unbeknownst to him, the other player’s roll differs. This concept can be a bit hard to grasp (and explain!), but it will hopefully become clearer once we illustrate a game tree.

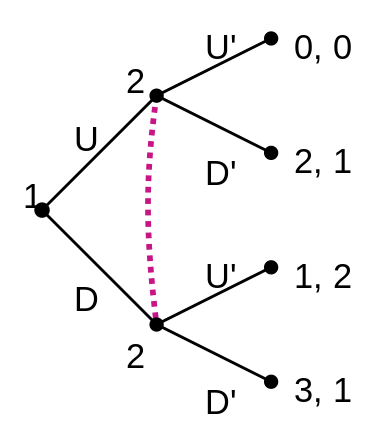

Image borrowed from Wikipedia

This shows a game with three decision nodes and four terminal nodes with payoffs for player1, player2.

Image borrowed from Wikipedia

This shows a game with three decision nodes and four terminal nodes with payoffs for player1, player2.

It also contains two information sets. One for player 1’s choice of U or D, and one for player 2’s choice of U’ or D’. The dotted line indicates that player 2 doesn’t know what player 1 chose. We can see that his payoff depends on it, though.

Let’s start coding

So, we’ve lined up some game rules and some concepts from game theory. Let’s see if we can turn this into some F#!

We’ll start with the players and a useful helper function.

type Player = | P1

| P2

let opponent = function

| P1 -> P2

| P2 -> P1

Next, we’ll model the different types of bets that can be made.

type Bet = | NoBet // No bet has been made. Not a valid bet and only used to signify the start of the game

| Bet of amount : int * die : int // A bet saying: there are atleast [amount] dice with the value [die] amongst us

| Call // Calling a bet, ending the game

We’ll also make a Roll type to represent the rolls of the players’ dice, and a Chance type that couples a probability with a Roll.

// Represents a roll of a die for each of the players

type Roll = { P1 : int; P2 : int }

type Chance = { Probability : float; Roll : Roll }

For testing who’s going to win when a bet is called, we need to have a function to check if a bet is valid, given the rolled dice.

// Tests if a Bet is valid given a Roll

let isBetValid (Bet(amt,die)) roll =

[roll.P1; roll.P2] // We'll take the rolled dice

|> List.filter ((=) die) // See which of them equal the bet

|> List.length // and count them.

|> (fun n -> n >= amt) // The count should then be greater than or equal to the bet amount

When the game ends, the players are going to get a Payoff. In our game it will just be 1 point or 0 points, but we’ll type it as a float for generality.

type Payoffs = { P1 : float; P2 : float }

The game tree

To model the game tree, we’re going to use a recursive discriminated union to represent a type Tree. Each instance of Tree represents a node and all of its children, plus additional information about the node.

I’ll show you the final Tree type here, and then I’ll explain the cases:

type Tree =

| Terminal of Payoffs

| Chance of chances : (Chance * Tree) list

| Decision of decidingPlayer : Player * roll : Roll * previousBets : Bet list * nextBets : (Bet * Tree) list

We’ll start with the easiest nodes, the terminal ones. These nodes don’t have any children, since this is where the game ends, and we’re only going to need information about the payoffs received to the players.

For the chance nodes, we will pair a list of Chance with a list of Tree, representing several random outcomes that descend into their own tree.

For the decision nodes, we’re going to need a bit more information. We’re interested in knowing whose time it is to make a decision, furthermore we need the dice that were rolled and the betting history. This information is needed to we can properly place the nodes in those information sets I mentioned above.

The bets the player can make are modeled similarly to the chance node, but here we pair a list of Bets with a list of Trees instead.

Constructing the tree

Before we get to the good stuff, I’m going to have to impose another little limitation. Usually, each die has 6 sides. Well, we’re going to limit this and start with 2-sided dice (coins, essentially).

let maxDie = 2

Now, let’s start by making a function to construct a terminal node. At this point in the game, a player has called a bet as untrue, and we need to settle the score using the Roll of the players’ dice.

// A bet has been called. This function takes

// The player who called the bet

// The players' rolls of the dice

// The bet that was called

let makeTerminalNode callingPlayer rolls bet =

let winner =

match isBetValid bet rolls with

| true -> opponent callingPlayer

| false -> callingPlayer

let payoffs = match winner with

| P1 -> { P1 = 1.; P2 = 0. }

| P2 -> { P1 = 0.; P2 = 1. }

Terminal(payoffs)

To make the decision nodes, we’ll need a little helper function. At a decision node, there will be a bunch of possible bets the player can make. These must be greater than the previous bet, so it seems natural that the function will be of the type Bet -> Bet list. With some sneaky use of the scanBack function, I got the following map:

let remainingBets =

let allBets = [ yield NoBet

for amt in 1 .. maxDie do

for die in 1 .. maxDie do

yield Bet(amt, die) ]

List.scanBack (fun x y -> x :: y) allBets []

|> List.tail

|> List.zip allBets

|> Map.ofList

Now we can make the decision nodes. Note that this is a recursive function, because decision nodes have more decision nodes as children.

// Player -> Roll -> Bet list -> Tree

let rec makeDecisionNode player rolls previousBets =

let previousBet = List.head previousBets

// Available bets out of this node

let availableBets = remainingBets |> Map.find previousBet

// Generates the decision node resulting if the player makes this bet

let genNextNode bet = makeDecisionNode (opponent player) rolls (bet :: previousBets)

// The children that result from making a bet from this node

let nextBets = availableBets |> List.map (fun bet -> bet, genNextNode bet)

match previousBet with

| NoBet ->

// If there hasn't been a bet yet, we're not allowed to call

Decision(player, rolls, previousBets, nextBets)

| _ ->

// We are in any other case though

let callNode = Call, makeTerminalNode player rolls previousBet

Decision(player, rolls, previousBets, callNode :: nextBets)

It’s not tail-recursive, but that won’t matter with this game, because it is not very deep.

All that’s left is to make the initial chance node, and we’ve got ourselves a game tree.

let tree () =

// All of the possible rolls of the dice, each with the same probability

let chances = [ for x in 1 .. maxDie do

for y in 1 .. maxDie do

yield { Probability = 1. / (float (maxDie * maxDie)); Roll = { P1 = x; P2 = y }} ]

// We take each dice roll and make a decision node based on it.

// P1 always starts, and the initial history is no bets

let children = chances |> List.map (fun chance -> chance, makeDecisionNode P1 chance.Roll [NoBet])

Chance(children)

I haven’t mentioned the information sets in a while. I’ll skip them partly because this is getting long, and partly because my solution for keeping track of them didn’t turn out all that idiomatic. It involved the m-word… The bad one :)

Analyzing with Gambit

I’ll also spare you the exercise of converting this tree into the EFG-format that Gambit uses and cut straight to the pretty pictures. Loading our game with 2-sided dice yields the following game tree

The green lines on the left represent the chance node that decides the dice, the red lines are player 1 and the blue lines are player 2.

Take note of the dotted lines going between some nodes. These represent that the nodes belong to the same information set. I.e. in both nodes, the player has the same amount of information to act upon.

Gambit now provides a method to “solve” the game and provide an equilibrium. It will then annotate the tree with the strategy each player should take for optimal play. Since the 2-sided dice version of this game is simple, the results are rather uninteresting. Basically, player 1 has a 50% chance of winning, since he will just take a guess at what player 2 has rolled.

Scaling up

Remember when I limited the game to 2-sided dice? There was a very good reason for that. The game tree for 2-sided dice has 125 nodes. For 3-sided, this goes up to 9,208. For 4-sided, we’re at 2,097,137. Going to 5 makes my computer run out of memory. This phenomenon is called combinatorical explosion, and it usually means you’re about to have a bad day at the office.

Now, the representation I’ve given of the tree is hardly the most memory efficient. And there is a ton of repetition in the structure which could be exploited.

However, the solver in Gambit is not equipped to handle such games, as it failed to solve even the 3-sided case on my computer overnight. So if we want to scale up to the real world case with 6-sided dice, we’re going to need to get creative.

Conclusion

In this post I’ve shown an application of F# that’s a bit different than what we usually see. It turns out that simple data types and a recursive discriminated union can provide a nice representation of the Liar’s Dice game tree.

Unfortunately the size of the problem prevents us from getting any interesting results out of Gambit for anything above the base case.

Thank you for tuning in, and feel free to comment if you’ve got any questions. I can also be reached on twitter: @KreutzSchmidt

Full code as a github gist: LiarsDice.fsx